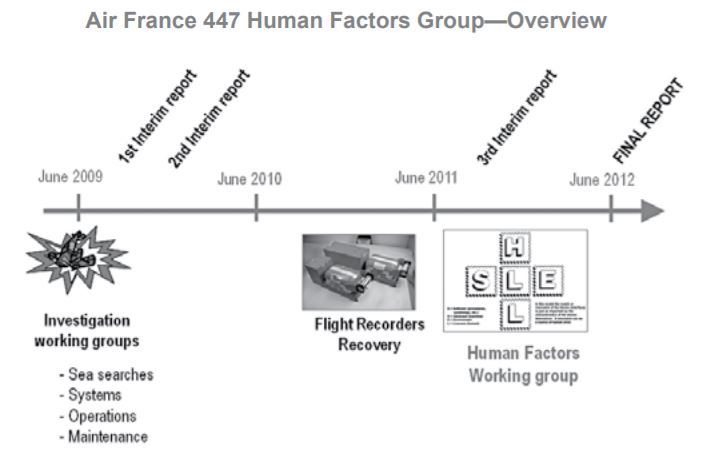

The aim of the Human Factors Working Group was to determine the set of safety provisions that affected the expected behaviors and skills of the crews in this situation. Based on the work already performed by the other working groups, and particularly since the download of the flight recorders in May 2011, a Human Factors (HF) Working Group was launched three months later.

The HF analysis was carried out by three Bureau d’Enquêtes et d’Analyses pour la sécurité de l’aviation civile (BEA) safety investigators and four HF experts, two of whom were pilots and provided the group with reasonable expectations that may be held regarding crew reactions and skills. The two other experts contributed their experience and their knowledge on the psychomotor, cognitive, social, emotional, and cooperative responses of human operators in general and of airline pilots in particular.

Coordination with other working groups was also essential to take into account the safety provisions that were supposed to guarantee the safety of the accident flight in the situation encountered. These provisions included, among others, explicit areas such as regulation, procedures to follow, and design features, which were designed to keep the flight safe.

They also included implicit areas that are more or less clear: basic airmanship, best practices, and reasonable expectations regarding crew behavior. The aim of the HF group was to determine the set of these safety provisions that affected the expected behaviors and skills of the crews in the situation of the accident. This involved identifying the failures that occurred during the flight, in relation to the explicit or implicit safety expectations. It also involved explaining these failures in the situation, by analyzing the interactions of the crew with the flight environment, the procedures available, and the information from the instruments and the airplane, as well as the interactions between crewmembers (the SHELL model).

Beyond the simple discovery of a psychologically probable, likely, or plausible explanation for the behavior recorded, the HF study also involved assessing the degree of specificity or generality of the behavioral responses recorded. Are they specific to this particular crew, shared by all the airline’s crews, or can they be generalized to all crews? With regard to human factors, the behavior observed at the time of an event is often consistent with, or an extension of, a specific culture and work organization. To put it another way, it involves answering the question: “If another crew were substituted for this one, would the same responses be observed?” The final aim is to contribute to identifying what should be modified in the whole of the safety provisions to significantly increase their effectiveness in a similar situation or in a generic situation including the same fundamental characteristics. For investigation authorities, the safety recommendations to be issued depend partly on the answer to the previous question.

Analysis

Close coordination with the investigator-in-charge and other working group leaders enabled the HF Working Group to close in February 2012. HF work was mainly used for the analysis part of the final report and particularly for the accident scenario. It notably brought out the fact that when crew action is expected, it is always supposed that the crew will be capable of initial control of the flight path and of a rapid diagnosis that will allow crewmembers to identify the correct entry in the dictionary of procedures.

A crew can be faced with an unexpected situation, leading to a momentary but profound loss of comprehension. If, in this case, the supposed capacity for initial mastery and then diagnosis is lost, the safety model is then in “common failure mode.” During this event, the loss of airspeed information due to obstruction of the pitot probes by ice crystals during cruise completely surprised the pilots of Flight 447. After initial reactions that depend upon basic airmanship, it was expected that the problem would be rapidly diagnosed by the pilots and managed where necessary by precautionary measures regarding the pitch attitude and the thrust, as indicated in the associated procedure. But the apparent difficulties with airplane handling at high altitude in turbulence led to excessive handling inputs in roll and a sharp nose-up input by the pilot flying (PF).

The destabilization that resulted from the climbing flight path and the change in the pitch attitude and vertical speed added to the erroneous airspeed indications and ECAM messages, which did not help the pilots diagnosis the situation. Thus, the crew’s initial inability to master the flight path also made it impossible to understand the situation Air France 447 Human Factors Group—Overview and to determine a solution. The crew, progressively becoming “destructured,” likely never understood that it was “only” faced with a loss of three sources of airspeed information. In the minute that followed the autopilot disconnection due to the obstruction of the pitot probes, the crew’s failure to understand the situation and the destructuring of crew cooperation fed on each other until there was a total loss of cognitive control of the situation.

The airplane then went into a sustained stall, signaled by the stall warning and strong buffet. Despite these persistent symptoms, the crewmembers never understood that they were stalling and consequently never applied a recovery maneuver. The combination of the ergonomics of the warning design, the conditions in which airline pilots are trained and exposed to stalls during their professional training, and the process of recurrent training did not generate the expected behavior. For example, recognizing the stall warning, even associated with buffet, supposes sufficient previous experience of stalls, a minimum of cognitive availability and understanding of the situation, and knowledge of the airplane (and its protection modes) and its flight physics. However, an examination of the current training for airline pilots does not, in general, provide convincing indications of the building and maintenance of the associated skills. Thus, based on the double failure of the planned procedural responses (loss of indicated airspeed and stall), the HF analysis was able to show the limits of the current safety model. This led to safety recommendations in the final report to notably improve crew training and the ergonomics of information supplied to the crews.