By Jan M Davies, Professor, University of Calgary; Martin Maurino, Technical Officer, Safety, Efficiency, and Operations, International Civil Aviation Organization; and Jenny Yoo, Advisor to the Korea Aviation and Railway Accident Investigation Board and Cabin Safety Analysis Group Chair, Korea Transportation Safety Authority, on behalf of the members of IBRACE.

(Adapted with permission from the authors’ technical paper titled The Passenger Brace Position in Aircraft Accident Investigation presented during ISASI 2017, Aug. 22–24, 2017, in San Diego, California, USA. The theme for ISASI 2017 was “Do Safety Investigations Make a Difference?” The full presentation can be found on the ISASI website

at www.isasi.org in the Library tab under Technical Presentations.—Editor)

The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) called upon subject-matter experts in the field of “brace-for-impact” positions to provide their advice to the ninth meeting of the ICAO Cabin Safety Group (ICSG/9) held in April 2016.

The ICSG/9 had the task of developing a new ICAO manual on safety-related information and instructions that should be transmitted to passengers. This manual includes a chapter on the brace-for-impact position, commonly referred to as the brace position. The ICSG required specific expertise and conclusions from internationally recognized studies in order to develop recommendations.

Representatives from the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Civil Aerospace Medical Institute; the Nottingham, Leicester, Derby, Belfast Study Group (which developed recommendations following the British Midland Airways Flight 92 accident); and TÜV Rheinland (which developed studies commissioned by the German government) were among the presenters.

Due to the different results presented by the experts, the ICSG noted that the studies did not lead to a single, universal recommendation about brace positions.

The group concluded further work was needed so that ICAO might provide a harmonized recommendation on brace positions. Therefore, ICAO formed the Ad Hoc Group on Brace Position, inviting the subject-matter experts and other stakeholders to carry out further work about recommended brace positions as a sub-group of the ICSG. In November 2016, 13 experts met at the Royal College of Physicians in London, England, to advance the work of the group.

During discussions, members noted the need to raise funds to support further research into the brace position, particularly for sled-impact tests. To fulfil this expanded mandate, members agreed to establish an independent group. Thus, the International Board for Research into Aircraft Crash Events (IBRACE) was founded.

The purpose of IBRACE is to produce an internationally agreed-upon, evidence-based set of impact bracing positions for passengers and (eventually) cabin crewmembers in a variety of seating configurations to be submitted to ICAO through the ICSG.

The 13 founding members brought with them a variety of backgrounds and expertise, including

- aviation (cabin safety and accident/incident investigation),

- engineering (sled-impact testing, aerospace materials, lightweight advanced-composite structures, and air transport safety and investigation),

- clinical medicine (orthopedic trauma surgery and anesthesiology), and

- human factors.

To date, the members of IBRACE have completed many tasks. Most importantly, members contributed content and illustrations

to Chapter 6, “Instructions for Brace Positions,” of the new ICAO Manual on Information and Instructions for Passenger Safety, First Edition, 2017 (Doc. 10086). Two Investigation questionnaires were also developed and are discussed later in this paper.

IBRACE members also developed and had posted the IBRACE Wikipage (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_Board_for_Research_into_Aircraft_Crash_Events).

In addition, searches have been initiated for funding and for research student(s). IBRACE is a not-for-profit board and has been self-funding to date. It’s vital that funding be found to support ongoing board activities and for research endeavors.

Question posed and aim of study

The theme of the 48th ISASI seminar was “Do Safety Investigations Make a Difference?” Overall there is no doubt that aviation safety has improved in the 109 years since the first aviation accident investigation. But what about passenger safety related to the passenger brace position? What can be learned from accident investigation reports about survival factors, particularly the passenger brace position?

This paper reviews U.S. Federal Aviation Regulations (FAR) Part 121 (scheduled air carrier) accident reports for 1983 to 2015 to look for passenger and cabin crew survival factors related to the emergency brace position.

Methods

This study had two parts. Part 1 involved a review of accident reports for 1983 to 1999, and Part 2 involved a review of accident reports for 2000 to 2015.

A decision was made to use the U.S. National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) report “Survivability of Accidents Involving Part 121 U.S. Air Carrier Operations, 1983 through 2000 Safety Report,” NTSB/SR-01/01, as the basis for the initial analysis.

Jan M. Davis

Jan M. Davis

has undertaken research in system safety in health care and aviation since 1983. Starting in the late 1980s, she spent more than a decade visiting the (former) Bureau of Air Safety Investigation, where she and Dr. Rob Lee, the director, codeveloped a systematic method to investigate anesthetic-related deaths. Together with Jim Reason, she and an anesthetic colleague were the first to apply the Reason model to a health-care investigation. In 1996, she finalized development of the model that underpins an evolution of her systematic, human-factors- based method for system-level investigations, Systematic Systems Analysis, now a University of Calgary certificate course.

The purpose of this NTSB report was to examine occupant survivability, with the twin goals of helping dispel the public’s perception that most accidents are not survivable and identifying factors to improve survivability.

Two concepts were defined in the NTSB report: “survivability” and “serious accident.” When talking about cabin safety, probably the most basic concept is that of survivability. A useful definition is one published by the NTSB in 2001.

The condition of survivability exists when the “forces transmitted to occupants through their seat and restraint system cannot exceed the limits of human tolerance to abrupt accelerations.” In addition, the “structure in the occupant’s immediate environment must remain substantially intact,” so as to provide a “livable volume throughout the crash sequence.”

Another definition relevant to this paper is that of serious accident. The same NTSB report stated that a serious accident was one in which there was a fire, either precrash or postcrash, at least one serious injury or fatality, and substantial aircraft damage or complete destruction of the craft. Rather than using the ICAO definitions of accidents, serious incident, and survivable crash environment, this definition was used because of the review of NTSB crash reports.

Part 1 (1983–1999)

Table 4 in the report provided a list of “fatality and survivor data, by individual accident, from NTSB investigation records for all Part 121 U.S. passenger flight accidents involving fire, serious injury, and either substantial airplane damage or complete destruction,” for 1983 through 1999. The list of accidents was used to find the corresponding NTSB investigation reports. These reports, where available, were searched manually and/or electronically, looking for two terms: “brace position” and “recommendations about the brace position.”

Martin Maurino

Martin Maurino

began his aviation career as cabin crewmember with Air Canada. In 2003, he joined the International Air Transport Association (IATA) as a safety analyst and in 2006 was appointed manager, safety analysis, responsible for accident analysis and publication of the annual IATA Safety Report. Maurino went on to join Transport Canada as the civil aviation program manager, working on implementation of safety management

systems, fatigue risk management systems, and human factors.

In 2010, he joined the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), and is the technical officer, safety, efficiency, and operations. He is responsible for all of ICAO’s cabin safety activities and acts as secretary to the ICAO Cabin Safety Group.

Part 2 (2000–2015)

A search was conducted of the NTSB investigation reports (where available) for Title 14 Code of Federal Regulations Part 121 U.S. passenger flight accidents for 2000 through 2015. As in Part 1, accidents in which suicide or sabotage was (thought to be) involved were excluded from the study.

A manual and electronic search was conducted for the same terms as in Part 1.

In addition, for all years, 1983–2015, a search was conducted for other accidents, that is, nonserious accidents, using the NTSB definition of serious accident. Again, the same search terms were used: the brace position and/or recommendations about the brace position.

Results

With respect to serious accidents, there were 26 between 1983 and 1999, with seven of these classified as nonsurvivable (one or fewer survivors).

Between 2000 and 2015, seven accidents were identified, five of which were considered nonsurvivable, using the same criteria as above.

Of the serious accidents between 1983 and 1999, only three of the 26 mentioned the brace position, and there were none in which recommendations about the brace position were made. These three accidents were

Jenny Yoo

Jenny Yoo

started as a cabin crewmember for a major international airline, holding various positions, including cabin crew team executive. In 2001, she earned a certificate in aircraft accident investigation and prevention from the Southern California Safety Institute. Subsequently Yoo joined the Air China 129 accident investigation (2002) and was the chair of the Survival Factors Group as well as the investigation report editor. She is an appointed advisor to the Korea Aviation and Railway Accident Investigation Board and an appointed Cabin Safety Analysis Group chair of the Korea Transportation Safety Authority. Yoo organized the Korean Society of Air Safety Investigators.

- United Airlines Flight 232 (Sioux City, Iowa, USA, 1989): Numerous mentions of the term brace were made. The captain “said that there would be the signal ‘brace, brace, brace’ made over the public address system to alert the cabin occupants to prepare for the landing.” (Page 22, Section 1.11.1, Cockpit Voice Recorder.) “All of the flight attendants and passengers were in a brace-for-impact position when the airplane landed.” (Page 40, Section 1.15.1, Cabin Preparation.)

- USAir Flight 405 (LaGuardia, New York, USA, 1992): “Prior to impact, passengers did not assume the brace position.” (Page 33, Section 1.15.1.2, The Passengers and Seats.)

- American Airlines Flight 1420 (Little Rock, Arkansas, USA, 1999): “Passengers also reported that the flight attendants yelled ‘brace’ to prepare for the impending impact.” (Page 54, Section 1.15.4, Passenger Statements.)

Between 2000 and 2015, there were no investigation reports of serious accidents in which the brace position was mentioned or recommendations made.

However, one additional report was found of an accident (that occurred between 1983 and 1999) not included in the NTSB report and in which there was a mention of the passenger brace position. This was

- USAir Flight 5050 (LaGuardia, New York, USA, 1989): “The flight attendants immediately reacted when they realized that the takeoff was deteriorating. As the airplane departed the runway’s deck, they told the passengers to brace.” (Page 53, Section 2.12, Survival Factors.) There were no recommendations about the brace position.

For the period between 2000 and 2015, two accident reports were identified

in which there were mentions of the brace position. These were

- JetBlue Flight 292 (Los Angeles, California, USA, 2005): “Prior to touchdown, the captain announced ‘brace,’ and the flight attendants also transmitted ‘brace’ over the public address system.” (Section 1.1, History of Flight.) “The flight attendants spoke to the passengers individually prior to the landing to ensure that each one knew the emergency procedures that would take place and how to properly brace.” (Section 1.15, Survival Aspects.)

- US Airways Flight 1549 (New York City, New York, USA, 2009): There are “numerous mentions of the brace position. slide/raft stowage; passenger immersion protection; life line usage; life vest stowage, retrieval, and donning; preflight safety briefings; and passenger education.”

One of the references to the brace position was with respect to the brace position shown on the safety card. “The airplane had safety information cards in the passenger seatback pockets that provided instructions on the operation of the emergency exits. A section of the card also shows the passenger brace positions.

The brace positions shown on the US Airways safety information card were similar to the current FAA guidance on brace positions, which is contained in AC 121-24C, Appendix 4, which states, ‘in aircraft with high-density seating or in cases where passengers are physically limited and are unable to place their heads in their laps, they should position their heads and arms against the seat (or bulkhead) in front of them.’ Two female passengers who sustained very similar shoulder fractures both described assuming similar brace positions—putting their arms on the seat in front of them and leaning over. They felt that their injuries were caused during the impact when their arms were driven back into their shoulders as they were thrown forward into the seats in front of them.”

The NTSB concluded that “the FAA’s current recommended brace positions do not take into account newly designed seats that do not have a breakover feature and that, in this accident, the FAA-recommended brace position might have contributed to the shoulder fractures of two passengers. Therefore, the NTSB recommends that the FAA conduct research to determine the most beneficial passenger brace position in airplanes with nonbreakover seats installed. If the research deems it necessary, issue new guidance material on passenger brace positions.”

A recommendation about the brace position was made. “Conduct research to determine the most beneficial passenger

brace position in airplanes with nonbreakover seats installed. If the research deems it necessary, issue new guidance material on passenger brace positions.”

Discussion

Definitions

Use of the term serious accident was based on the review of accidents listed in the NTSB report. In that report, the safety board reviewers determined that passenger and crew survival was “never threatened” in the majority of Part 121 accidents up to the end of 1999. The safety board therefore focused on the “survivability in serious accidents” and determined that, as with all Part 121 accidents, most occupants survived the “serious survivable accidents”

There is a difference between this NTSB term and definition and the ICAO terms and definitions. ICAO’s Annex 13 defines an accident as an “occurrence associated with the operation of an aircraft that, in the case of a manned aircraft, takes place between the time any person boards the aircraft with the intention of flight until such time as all such persons have disembarked, or in the case of an unmanned aircraft, takes place between the time the aircraft is ready to move with the purpose of flight until such time as it comes to rest at the end of the flight and the primary propulsion system is shut down,” in which a person is fatally or seriously injured…, the aircraft sustains damage or structural failure…, or the aircraft is missing or is completely inaccessible. A “serious incident” is defined as an “incident involving circumstances indicating that there was a high probability of an accident.” ICAO does not define a serious accident.

The decision was made to use the NTSB term and definition because of the review of accidents for 1983 to 1999 listed in the NTSB 2001 report. The same definition was therefore used for the review of accidents for 2000 to 2015.

Results

Accident investigation findings and recommendations have helped improve aviation safety. In the course of the study, it was noted that most investigation reports make no mention of, or recommendations about, the brace position. However, the authors of the NTSB report determined that in serious accidents for the period 1983–1999, fatalities related to the impact of the crash were about five times more frequent than fire-related fatalities. One implication of this finding is that more passengers might have survived had they assumed and maintained an appropriate brace position. In addition, more can be learned from accident investigations that focus on survival factors. For example, changes to passenger seating and cabin configurations influence how passengers brace for impact. During the discussion at the latest IBRACE meeting, members noted that it would be impossible to conduct any sled-impact testing in seats with a 28-inch pitch and using the standard Hybrid III dummy because it would not fit.

Therefore, it is important for investigators to look for survival factors, for example, an appropriate brace position. Currently, sources of information for accident investigators include survivors’ testimonies, medical or pathological information, and evaluation of various brace positions’ usefulness in surviving an accident. However, accident investigators need additional tools to obtain survival information.

Additional tools

Recently, ICAO released the new Manual on the Investigation of Cabin Safety Aspects in Accidents and Incidents (Doc. 10062). This document includes recommendations to ask survivors about such details as seat belt use and brace position adopted. However, accident investigators might find it helpful to have more detailed questions. IBRACE therefore developed two new questionnaires: the illustrated Survivors’ Questionnaire and the Deceased Questionnaire.

The Survivors’ Questionnaire is for completion by survivors, either with or without assistance from investigators, and has 18 questions—most with diagrams.

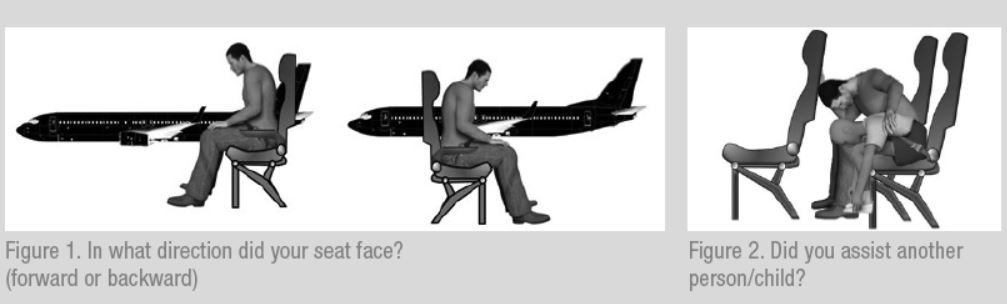

Two typical questions are “In what direction did your seat face? (forward or backward)” (see Figure 1) and “Did you assist another person/child? (yes or no)” (see Figure 2).

The Deceased Questionnaire pertains to deceased victims, for completion by accident investigators and medical/forensic personnel, and has 10 questions but no diagrams. Typical questions include “Was the deceased seated at the time of the accident (yes or no).” “If yes, was the seat belt buckled at the time of the accident? (yes or no).” “Were there any clothing imprints on the skin overlying the lower abdomen, iliac crests, greater trochanters, or upper thighs? (yes or no).”

These questionnaires have three goals: to assist investigators in their findings and recommendations about survival factors, to gather information about brace positions, and to assist in developing evidence-based recommendations for brace positions for passengers and cabin crewmembers.

Conclusions

The review of NTSB reports of 34 accidents, between 1983 and 2015, included mention of the brace position in five reports and recommendations about the brace position in only one report. One of the goals of IBRACE is to encourage investigators to gather, analyze, and incorporate information regarding the brace position in accident reports, using standardized questionnaires.

IBRACE also aims to contribute to the better understanding of survival factors and thus to develop and implement recommendations about them. This, in turn, should contribute to a reduction of passenger and cabin crew fatalities and injuries, thus leading to further improvements in aviation safety.

IBRACE also aims to contribute to the better understanding of survival factors and thus to develop and implement recommendations about them.