Whether you fly a huge Airbus A380 or a petite Cessna 150 they both basically operate in a similar manner in terms of flying technique – “Push and the houses get bigger – Pull and the houses get smaller – Keep pulling and the houses start to get bigger again”!! That maybe a simplistic view but what that phrase is talking about is attitude and the effect a control input has on attitude and the end result. The aircraft attitude, coupled invariably with a power setting, is normally one of the first things an instructor will teach you using the famous APT (Attitude, Power, Trim) and PAT (Power, Attitude, Trim) for various stages of flight.

In a modern commercial airliner those basics are quite often forgotten as pilots rely heavily on the automation and the Flight Director (FD) system. They forget that if they looked at the attitude indication then their aircraft obeys all the same principals as the first small aircraft they flew. As an example, just about every commercial airliner I know has a cruise attitude of between 2° and 3° nose up with a power setting something above 70% maximum thrust. For a climb, power is increased, pitch attitude increased, and aircraft retrimmed (normally automatically), thereby following the PAT.

For a level off, attitude is reduced back to cruise datum, power is reduced to maintain cruise speed, and the aircraft retrimmed (normally automatically), thereby following the APT. With the autopilot and autothrust/autothrottle engaged all of this is done for you but the aircraft is still following the same technique.

Attitude is the key and knowing what attitude to expect, or set, for the various stages of a flight is a key airmanship skill that sadly seems to be deteriorating. Two tragic accidents clearly show this and one of them is similar to the recent UAE registered B737 accident.

AIR FRANCE 447 – Airbus A330-200 – June 2009 – South Atlantic

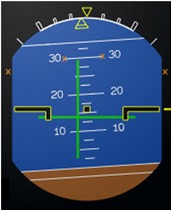

This well documented accident, where 228 people were killed after the aircraft entered a deep aerodynamic stall while in the cruise at FL350, is a classic example of the pilots not flying the aircraft following a malfunction and not looking at the attitude. The aircraft was in a stable state with a pitch attitude of approximately 2.5° nose up and a relatively steady power setting.

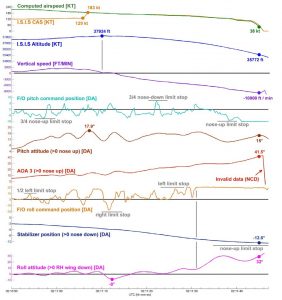

Following the blockage of the pitot system by ice crystals, resulting in unreliable airspeed indications, the autopilot and autothrust systems disconnected. In the following few seconds the co-pilot pulled back on the sidestick setting a nose up attitude of 12° which resulted in a rate of climb of nearly 7,000 feet per minute (fpm) and the airspeed rapidly decaying from 274knots to 52knots with a high angle of attack. The aircraft climbed 3,000ft until it entered a stall and began a 10,000fpm decent to eventually impact in the Atlantic Ocean. Throughout the 4 minutes from the loss of airspeed indications to the impact, the Primary Flight Display (PFD) was indicating correctly the very high nose attitude which was way above the normal cruise or cruise climb attitude.

|

|

AF447 pitch attitude indication towards the top of ‘zoom’ climb and entering stall. Note confusing Flight Director indications. |

AF447 Graphical data. Note the pitch attitude (17.9° nose up) as the aircraft enters the stall and the pitch up command by the pilot, which is full nose up when fully stalled and descending at 10,000fpm. |

In hindsight it is easy to judge the actions of the crew, but what we should learn from this accident is that perhaps a lack of attitude awareness by this crew, and potentially many other commercial airline pilots, is something that needs to be highlighted. There are unreliable airspeed procedures, memory items, for the various aircraft types which basically say set a particular attitude and power depending on aircraft configuration. This action gives time to get the published tables out to then set attitude and power for the required flight path. It is possible to use these published tables to get the aircraft safely back on the ground with no airspeed indications at all!

Tatarstan 363 – Boeing 737-500 – November 2013 – Kazan

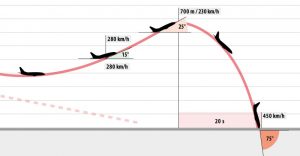

This tragic accident, that killed 50 people, occurred following a go-around where having initiated the go-around by pressing the TO/GA switch the autopilot disengaged. No manual control inputs were made and the pitch attitude increased to in excess of 25° nose up with speed decaying to 117knots. Due to control inputs by the crew and the trim system the pitch angle decreased quickly and resulted in a final attitude of 75° nose down. It is believed that the pilot may have been a victim of a pernicious form of disorientation called “somatogravic illusion” which led him to believe the aircraft was climbing despite the attitude indicator clearly showing a significant nose down indication.

There have been other similar accidents of pilot disorientation following a go-around resulting in the aircraft crashing including Gulf Air 072 at Bahrain in 2000 and Armavia 967 at Sochi in 2006.

|

|

Tatarstan 363 accident Site – Kazan Airport |

Tatarstan 363 (B737-500) Go-around profile. |

Believe Your Instruments

Many years ago (1975) when I started my military flying, and then later teaching military pilots, a lot of emphasis was placed on disorientation and believing your instruments. I distinctly remember the instructor telling me to close my eyes while he performed a series of aerobatics that ensured I was totally disorientated then gave me control to recover the aircraft to straight and level flight using my instruments. If I was lucky the attitude indicator had not toppled and could be used but I was also taught how to use other instruments to help me recover the aircraft to level flight. The key learning point was to believe your instruments, not what you were sensing.

Modern commercial aircraft have extremely reliable attitude indicators and it is very unlikely that a pilot would be left without correct attitude information. The pitot and static systems are more likely to provide incorrect information, as happened to AF447, but the recovery procedure in event of such a failure is to set an attitude and power to give a safe stable state and time.

Attitude is a Life Saver

Knowing the various pitch attitudes, and power settings, for your particular aircraft type in different phases of flight is an airmanship skill all pilots should have and regularly practice. Whilst maximum use of automation definitely enhances safety pilots need the skill to be able to safely fly the aircraft when the automatics are not available, as in AF447.

“The manufacturer’s published airspeed unreliable pitch attitude and thrust settings could be considered as an initial recovery combination in any situation”.

You may consider that a bold statement but look at the accidents above and apply that. In the AF447 case setting 5° nose up and Climb thrust would not have resulted in the aircraft zoom climbing and entering a stall. In the Tatarstan case, and the other go-around accidents mentioned, maintaining approximately 15° nose up attitude and re-engaging the autopilot, or setting a level flight nose up attitude and power and re-engaging the autopilot, would have given the time for the pilots to recover from the disorientation.

Effective Training

Regular practice in flying your particular aircraft type without the automatics helps to maintain and sharpen the airmanship skills of flying the correct attitudes and power settings. I believe that some airlines actually include an additional, non-jeopardy, simulator session each year specifically to re-enforce manual flying skills and in my opinion that is to be commended. Perhaps all airlines should include more manual flying practice in the simulator, rather than constantly repeating exercises using the automation.

Manual flying on the line does have some risk associated with it which is why some airlines advocate ‘maximum use of automation’. Disconnecting the autopilot at top of descent in an airliner with 400 passengers onboard to fly an approach to an airport with a low cloudbase may not be the best time to practice manual flying! On a CAVOK day then perhaps the whole approach, including the turn onto finals, could be flown manually. Remember that as soon as the autopilot is disconnected the workload of the Pilot Monitoring increases dramatically! As a minimum consider looking at and memorizing the approximate attitudes and power settings that the aircraft flies for the different phases of flight because it might come in useful one day.

Good Airmanship Enhances Flight Safety

You may read part 1, “Airmanship 1, Situational Awareness – Final Approach” here:

https://www.menasasi.org//main/node/392/

Written by: Captain Tony Wride, Manager Safety Risk, Etihad Airways

Published on: The Investigator Magazine, Volume 1, Issue 11, October 2018