The need to look at Human Factors at the very beginning of any automated project to clarify role sharing

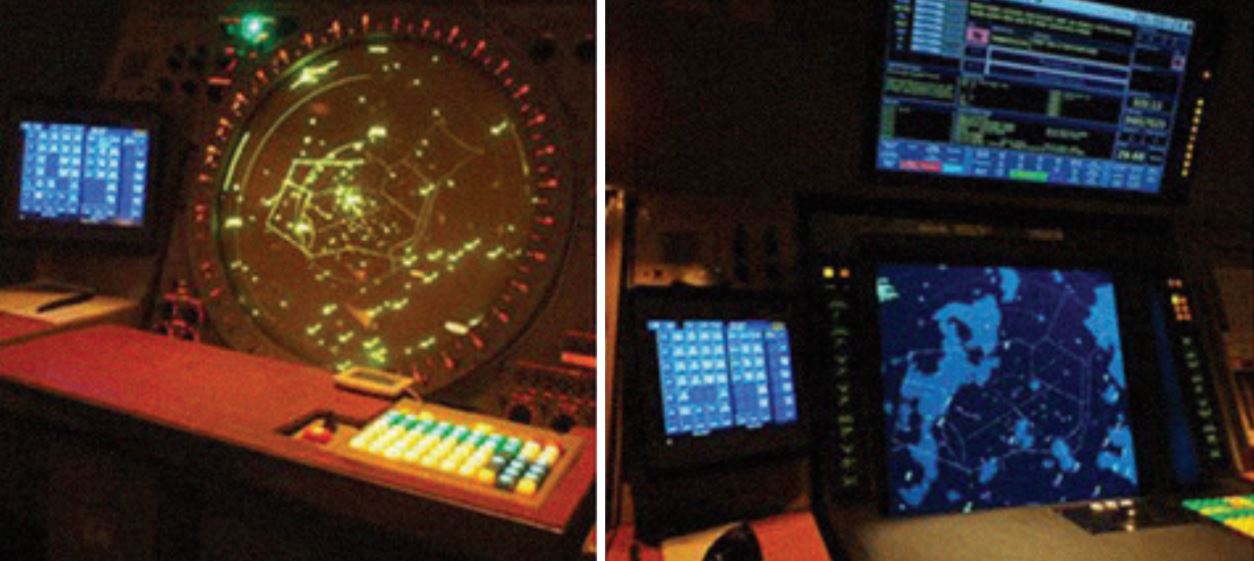

I STARTED MY career in Air Traffic Control on a cold morning in January 1988. At the time, Primary radar was in use with aircraft radar returns looking like electronic insects creeping about on an orange cathode ray tube.

W R I T T E N B Y

JAMES FAIRLEY,

Air Navigation Services Safety Specialist,

GCAA

UAE

Controllers spoke constantly to each other across a pitch-black smoke filled room (yes you could smoke in radar rooms then) to ask what each other’s aircraft were doing. There was no speed or height displayed on any screen. Any potential coordination was passed down theroom by pen and paper. When something got a little too close for comfort then you stood up and shouted to your partner in crime alerting them to the situation. Move forward into the 90’s and Secondary Radar gave the controller that warm and fuzzy feeling of always knowing which aircraft belonged to who and slowly but surely my automation relationship in ATC began to evolve.

Like any relationship, it takes time to understand how the other partner functions. We do not always understand each other’s views or why we do things differently and it is no different with automation. This lack of understanding can lead to a mistrust of the automation in some but also an over reliance in others. Fast forward to the present day and we could honestly say that automation is at the core of everything we do in ATC, as well as in our day-to-day lives.

We use the phrase ‘The Human in the Loop’ or ‘Human in the System’ quite a lot in regards to Safety Management Systems and the human interaction with machine intelligence.

ICAO gives guidance in various documentation from Human Factors Training in Doc 9683, Guidelines for Air Traffic Management Systems Doc 9758 and many more. The following is an extract from Doc 9758 about approaches to automation:

‘A technology centered approach automates whatever functions it is possible to automate and leaves the human to do the rest. This places the operator in the role of custodian to the automation; the human becomes responsible for the ‘care and feeding’ of the computer. A human centered approach provides the operator with automated assistance that saves time and effort; the operator’s task performance is supported, not managed, by computing machinery. ‘

At present, a dominant thinking trend is visible that everything can be easily automated by computers, robots and with use of AI software. However, the question of what and how to automate is, within a specific context, not always that simple. The more automation that is added to a system, and the more reliable and robust that automation is, the less likely that human operators overseeing the automation will be aware of critical information and be able to take over manual control if needed. It is no longer about the ‘Human in the Loop/ System’ but about the ‘human getting lost in the system maze’ as if it were never-ending and continually growing bigger and bigger as automation evolves.

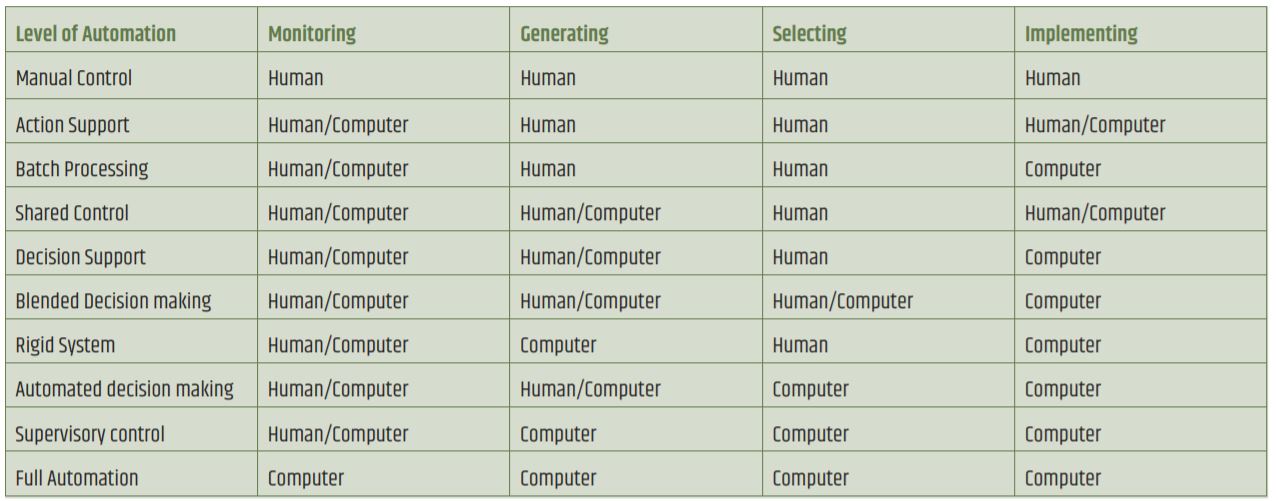

Levels of automation by Endsley and Kaber (1999) shows the corresponding role played by the human and or the computer in functionality. This demonstrates the complexity of the relationship when focusing on a decision and action methodology in automation. It is certainly not as simple as looking up the table and assigning the role as per a corresponding box especially when

it comes to the inter dependency of both the human and the computer. This confirms there is a need to look at human factors at the very beginning of any automation project to clarify how a role may be shared.

Prior to introducing any new automation into any system there should be a clear set of Human Factors objectives set:

ATC places the operator in the role of custodian to the automation; the human becomes responsible for the “care and feeding” of the computer.

- transparency of underlying software operations;

- – a controller should be able to carry out tasks naturally or intuitively. Computer programming convenience should not take priority over usability.

- error-tolerance and recoverability;

- – design should be able to anticipate possible user error in data entry e.g. “are you sure you want to delete this flight plan?”

- consistency with controller’s expectation;

- – automation should take into account ATC procedures and operations e.g. local airspace traffic management restrictions.

- compatibility with human capabilities and limitations;

- – failures within the automation should be easily identifiable to the controller.

- Controllers should not have to passively monitor the automation to detect failure.

- ease of reversion to lower levels of automation and of returning to higher levels of automation;

- – operating highly automated systems over a long period of time can cause skill fade of the basic controller tasks such as situational awareness.

- ease of handling abnormal situations and emergencies; and

- – controllers should have access to critical flight information regarding all aircraft in their sector.

- ease of use and learning

- – a system that is complex needs extensive initial training as well as extended recurrent training.

What can we learn from the human – automation relationship? Understanding what is involved from both parties is always key, which in turn will build trust. Trust is always the fundamental foundation of any relationship. We need to ensure that the human factor is forefront in any development of automation, more so as we move into the Artificial Intelligence era.

Ensure that we stay informed, or in the loop, of emerging technology and then you will be less likely to be lost in the system maze. Question whether the automation is needed. Will this further automation degrade the controller’s ability to carry out even the simplest tasks? Finally, what would you do if the automation failed? How confident would you feel if you walked into a modern day version of my 1988 operational environment?

Written by:JAMES FAIRLEY, Air Navigation Services Safety Specialist, GCAA, UAE

Published on: The Investigator Magazine, Volume 2, Issue 14, March 2020